Psychologists take different approaches, or perspectives, when attempting to understand human behavior. For instance, psychologists taking the biological approach assume that differences in behavior can be understood in terms of genes, brain structure and hormones, which can predispose a person to particular health conditions.

Behavioral psychologists emphasise the role of the environment on a person’s behavior, and believe that we learn new behavior as a result of conditioning. They maintain that parenting styles, teaching and life experiences all help to shape us as individuals. The cognitive and psychodynamic approaches look inwards, focussing on the thoughts and other cognitive processes that lead a person to behave as they do.

Different approaches in psychology offer contrasting explanations for many issues. Taking a biological approach to understand the causes of schizophrenia, for example, one might refer to twin studies, which have indicated a genetic component to the disorder. However, the behavior approach emphasizes the correlations between schizophrenia and being raised in a city as opposed to the countryside (Lewis et al, 1992).

Of course, both genetic and environmental factors often influence the same issue, and so each of the explanations given by various approaches can help us to further our understanding in psychology.

Below, we summarise and evaluate five key approaches:

Physiological Approach (Biological)

The physiological approach assumes that biological factors influence our behavior and mental well-being in a cause-and-effect manner, in the same way as exposure to a disease can lead to illness. Biological factors include genes, inherited from a person’s parents, which psychologists believe can influence whether they are predisposed to some conditions.

The biological approach also focuses on the physical processes that occur within the central nervous system (CNS), which comprises the brain and spinal cord. Neuroscientists have found that different areas of the brain serve specific functions, supporting influence of the brain’s structure on people’s behavior. For instance, the temporal lobe assists in the processing of language, whilst the frontal lobe plays a role in our experience of emotions.

As technological advancements have improved scientists’ ability to investigate processes occurring within the brain, they have been able to identify the role played by specific regions of the brain. The amygdala helps us to store memories and to experience emotions. Maguire et al (2000) found that the hippocampus, which serves important memory functions, was larger in the brains of London taxi drivers, who are required to store vast amounts of street information in order to fulfill their job.

This study demonstrates how the brain can respond to changing conditions, such as the need to remember information, with biological adjustments known as neuroplasticity.

The biological approach also seeks to understand humans as a collection of chemical reactions. For instance, research suggests that levels of neurotransmitters in the brain such as serotonin play a role in depression.

Hormones circulating in the bloodstream and other organs can also influence our behavior. Cortisol is released at times of stress in preparation for a fight-or-flight response to a threat. Other hormones help to regulate biological rhythms, such as the menstruation cycle in females. Melatonin helps to us to maintain a regular sleep-wake cycle, resulting in a feeling of tiredness late in the evening.

Compared to other approaches, biological perspectives such as the physiological approach adhere the closest to established scientific methods of studying the human mind. The approach relies upon the observation of humans and other animals in experiments. The validity of findings derived from experiments can be tested by other psychologists, owing to their replicability.

Brain imaging techniques such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), functional MRI (fMRI) and computed tomography (CT) scans play an increasingly significant role in the investigation of processes occurring within the brain.

The physiological approach’s strengths lie in its reliance on empirical findings from experiments and its falsifiability. Unlike the psychodynamic theories of Freud, hypotheses can be proven or disproven.

The biological approach has led to important developments in the production of drug-based therapies for the treatment of disorders such as depression. However, questions remain regarding the success and ethics of other physiological procedures such as lobotomies, where the connections between sections of the brain are severed, and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT).

Critics view the physiological approach as reductionist, as it ignores the complexities and unpredictability of humans, their personalities and their behavior. The approach also ignores to an extent environmental influences, such as learned behavior.

Learn more about biological approaches here

Evolutionary Approach

The evolutionary approach also looks to a person’s biological composition in order to understand their behavior. But, where physiological explanations cite activity within an individual and their brain, the evolutionary approach assumes that the mind has been fine-tuned in response to its environment over many millions of years.

A general theory of evolution was proposed by Charles Darwin in his 1859 book On the Origin of Species. Darwin’s ideas were in part the result of a trip to the Galápagos islands. Whilst comparing the anatomy of birds across the islands, he found that the shape of their beaks varied depending on the environment of the island on which they lived. He concluded that the birds, which would eventually be known as Darwin’s finches, had changed from generation to generation, in response to their habitat.

The shape of the birds’ beaks had adapted to enable them to forage for food available to them more effectively.

This adaptation is the result of natural selection, whereby optimally adapted individuals are able to feed more, and stand an increased chance of reproducing to produce similar offspring. Similarly, traits which are desirable in a partner are more likely to be passed to further generations as a result of sexual selection.

Evolutionary psychologists believe that the principles of evolution can be used to understand human behavior. Many consider the experience of stress to be a result of humans’ adaptation to survive predators. As part of the fight-or-flight response to a threat, the body will adopt a state of alertness in preparation to fend off an aggressor or to escape them. Today, however, stress no longer serves as significant survival advantage as it would have to our earlier ancestors.

Like the physiological approach, evolutionary psychology provides credible evidence explaining why we behave as we do. However, the approach has been criticised for being reductionist and for failing to account for the individual differences amongst different people.

Learn more about the evolutionary approach here

Behavioral Approach

The behavioral approach assumes that each person is born a tabula rasa, or blank slate. Rather than being influenced by genes and biological processes, behaviorists believe that our outward behavior is determined by our external environment. A person learns from his or her life experiences and is shaped to behave in a particular way as a result. Behaviorists look at the behavior a person exhibits, rather than the inner processes of the mind.

Radical behaviorist John B. Watson (1878-1958) set out the principles of the behavioral approach in a 1913 paper entitled Psychology as the Behaviorist Views It, which would later be described as the ‘behaviorist manifesto’. He emphasised the “objective” nature of the approach, believed that scientific methods could be applied to human behavior, and that a person’s behavior could be observed, measured and quantified through experimentation (Watson, 1913).

Behaviorists focus on conditioning - both classical and operant forms - as a form of learning. Conditioning involves the use of a stimulus to evoke a desired response - a particular type of behavior - from a person or animal. Animal trainers, for instance, provide dogs with the prospect of a treat (a stimulus) to reward good behavior (the conditioned response).

Research into classical conditioning was pioneered by physiologist Ivan Pavlov (1849-1936). In laboratory experiments with dogs, a researcher would open a door to feed the animals.

Instinctively, the dogs would salivate at the sight of food.

However, Pavlov observed that the dogs would salivate when the door opened, even when no food was provided. The dogs had begun to associate the opening of the door with the receipt of food. In time, the door - an unconditioned stimulus - had become a conditioned stimulus, evoking the dogs’ conditioned response of salivation.

In 1905, Edward Thorndike identified an alternative form of conditioning in cats, which he described as the law of effect. B. F. Skinner also observed this behavior in pigeons, referring to it as operant conditioning. In an experiment where pigeons were fed periodically through a mechanism in a ‘Skinner box’, he observed that the birds learnt to enact particular types of behavior, such as turning counter-clockwise, prior to receiving food. The food was a positive reinforcer of their behavior (Skinner, 1948).

During operant conditioning, one learns to adopt a particular behavior as a result of reinforcements or punishments. Positive reinforcements involve a desirable reward such as food. The lessening of an undesirable stimulus is a negative reinforcement.

Punishments can also facilitate operant conditioning. The imposition of an undesirable event, such as the ringing of an alarm, is a positive punishment, whilst a negative punishment involve depriving someone of something that they desire.

Whilst conditioning plays an important role in learning, Skinner noted that responses to stimuli would not continue indefinitely. If a subject provides a conditioned response but does not receive the stimuli for a period of time, this conditioned behavior disappears through extinction.

The behavioral approach adopts similar scientific principles to the biological approaches. Evidence is gathered through the observation of behavior, including in experiments involving humans and animals.

However, the extent to which the observation of non-human behavior can be applied to humans is questionable. The behavioral approach is also reductionist in its emphasis on behavior, failing to account for internal activities which are more difficult to observe, such as thoughts and emotions.

Moveover, it does not explain the individual differences in behavior that can be observed amongst individuals who have experienced similar environments.

Behavioral research has many practical applications in situations where learning takes place. Its findings have advanced developments in teaching, and have led to the invention by Thomas Stampfl in 1967 of flooding (also referred to as exposure therapy) as a means of conditioning phobics to accept stimuli which they would otherwise be fearful of.

Learn more about the behavioral approach here

Cognitive Approach

The cognitive approach takes a different view of human behavior to the behaviorists. Instead of simply observing behavior, it looks at the internal, cognitive processes that lead a person to act in a particular way.

The cognitive approach was described by Ulric Neisser in his 1967 work Cognitive Psychology, and focusses on issues such as the encoding, consolidation and retrieval of memories, emotions, perception, problem-solving and language.

Cognitive scientists often use the metaphor of the brain functioning in a similar way to a computer. Just as a computer processor retrieves data from a disk or the internet, the brain receives input signals: visual input from the eyes, sound from the ears, sensations via nerves, etc.

The brain then processes this input and responds with a particular output, such as a thought or signal to move a specific muscle. This computer analogy of the brain can be seen in many cognitive explanations of the human mind.

Cognitive psychologists consider the way in which existing knowledge about people, places, objects and events, known as schemas, influence the way in which we perceive and think about encounters in our day-to-day lives.

Schemas develop as a result of prior knowledge, and enable us to anticipate and understand the world around us. In a famous experiment known as the War of the Ghosts, psychologist Frederic Bartlett revealed the reconstructive nature of memory, with its use of schemas to recall past events (Bartlett, 1932).

Whilst cognitive processes are challenging to measure, the cognitive approach uses scientific methods, including experiments which aim to reveal our internal thoughts through our actions.

In one such experiment, Loftus and Palmer (1974) presented participants with a video showing a car crash and asked questions regarding the incident, leading respondents towards a particular answer.

The results demonstrated the dynamic nature of memory recall and how present events can influence a person’s recollection of the past.

Cognitive psychology research into memory would later lead to the development of the cognitive interview, which aims to improve the accuracy of eyewitness testimonies. Numerous theories of memory have also been produced, including the working memory model (Baddeley and Hitch, 1974) and the multi-store model (Atkinson and Shiffrin, 1968).

Learn more about the cognitive approach here

Humanistic Approach

After the psychodynamic approach and behaviorism, the humanistic approach is considered to be the “third force” in psychology. It emerged in reaction to previous approaches, rejecting the reductionism of human behavior to a set of stimuli and responses proposed by behaviorists.

Humanistic psychologists felt that such an approach ignored the human motivations which drive us, and the free will that we experience to make decisions independently. They believed that behaviorism focussed too heavily on quantitative research and scientific methods such as experimentation, measuring responses to produce statistics which account for groups’ behavioral tendencies, but which failed to understand the true nature of the individual.

The humanistic approach also rejected the determinism of the psychodynamic approach, with its assumption that the subconscious and its innate drives lead to a person’s behavior, rather than his or her free will.

Instead, the humanistic approach assumes that individuals possess some degree of self-control, are capable determining their own behavior. Whilst beliefs, values, morals and goals influence our actions, we possess free will and are ultimately responsible for our behavior.

Humanistic psychologists acknowledge the unique individuality of each person, and accept that subjective experiences contribute towards our personalities and our behavior.

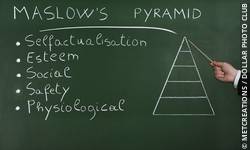

Abraham Maslow (1943) developed a Hierarchy of Needs, describing the motivations that drive each of us.

These range from survival needs, such as the desire for food, up to a need to achieve and reach one’s potential. Maslow termed such goals self-actualizing needs, and claimed that our behavior is driven by these needs. Obstacles hindered a person’s desire to achieve such goals can lead to them suffering.

Following humanistic principles, Carl Rogers developed client-centered therapy, and advocated that the therapist build rapport with a client, listening to and empathising with them. Rather than providing harsh criticism, Rogers proposed that the therapist exhibits unconditional positive regard for the client, regardless of their attitude.

The humanistic approach emphasises the importance of qualitative evidence over the quantitative, statistical measurements of more scientific approaches. Individuals may be interviewed and allowed to express their true feelings. Open-ended questionnaires may also be used, as may client observations and diary-keeping.

The q-sort method is another humanistic research technique.

A person is given two identical deck of cards containing self-descriptive adjectives and phrases. They are asked to sort the first deck in order of how accurately the cards describe themselves at present. They then arrange the second deck in order how they would like to be in an ideal world - their actualised self. Differences in the position of the same card between decks reveal potential opportunities for personal development.

The approach satisfies the demand for more humanistic values in Western societies and has resulted in numerous practical applications. For instance, Rogers’ methods of client-centered therapy have influenced modern-day counselling techniques. Self-help books and seminars also aim to cater for our need to achieve actualization.

In contrast to biological and psychodynamic perspectives, the humanistic approach acknowledges the individuality of human beings, along with the free will indicated by our conscious thoughts.

Yet, humanistic psychology lacks the empirical evidence that the physiological approach is able to obtain through experimentation. It also ignores the significant value of biological approaches, including the role played by genes and neurochemistry in influencing behavior.

Learn more about the humanistic approach here

Psychodynamic Approach

The psychodynamic approach emphasises the role that the internal ‘dynamics’ of a person’s personality play on his or her behavior. These include the innate drives which we are born with, but remain unconscious of.

At times, these drives result in the potential for undesirable or socially unacceptable behavior. Therefore, the mind tries to silence desires, such as sexual drives, by repressing them. However, repression does not eliminate a person’s impulses, and internal conflicts can surface as seemingly unrelated problems later in life.

The psychodynamic approach was popularised by the writings of Austrian physician Sigmund Freud (1856-1939). Freud’s publications, which included case studies and psychodynamic theories on issues such as the human psyche and humor, have led to him being regarded as the father of psychoanalysis.

Freud identified 5 stages of psychosexual development, during which a person derives satisfaction from a different area of the body, or erogenous zone. These stages include the oral stage during feeding, as an infant enjoys comfort from drinking milk. The later anal stage encompasses a period of toilet training.

Freud believed that if a person was prevented from fulfilling their needs at any stage, a fixation involving the relevant erogenous zone could occur. For example, if an infant is unable to feed properly during the oral stage, according to Freud’s theory, they may later develop a habit of nail biting or smoking.

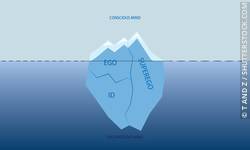

Additionally, Freud proposed that the human psyche is comprised of three competing entities: the id, ego and super ego. The id drives impulsive desires, whilst the ego tempers such desires with the external realities of potentially being punished for behaving irrationally. The super ego is aware of a person’s actions on others, and is responsible for feelings of guilt and regret.

More controversially, Freud proposed that males suffer from an Oedipus complex - a desire for their mother which results in a resentment of their father. Similarly, he believed that females desire their fathers, as part of an Electra complex.

The psychodynamic approach also regards human behavior as being motivated by a desire to ‘save face’ - to preserve one’s self esteem and sense of worth. Thoughts threatening to the ego are confronted with the deployment of defense mechanisms, which include repression, sublimation and the transference of feelings from one person to another.

Freud is credited for bringing attention to the influence of subconscious thoughts and desires on the human psyche.

However, the study of such drives is impossible to objectively observe.

Instead, Freud used psychoanalysis in an effort to gain accounts of his patients’ conditions. He focussed not only on their present condition but used free association, hypnosis and regression to explore their childhood experiences, their relationships with their parents and with other family members.

Freud’s cases, which consisted primarily of middle class women living in Vienna during the early 20th Century, led to him publishing a series of papers. These including case studies, such as that of Little Hans (Freud, 1909). He also wrote that hysteria in the case of Anna O, a client of his colleague, Josef Breuer, could be explained using a psychodynamic approach (Freud, 1895).

Freud’s theories became incredibly influential at the time of their publication, but in later decades, psychologists began to questions some of his ideas. His reliance on selective aspects of case studies were the only evidence Freud used to support his theories. Theories regarding the psyche are also difficult to prove and cannot be falsified.

Focussing on subconscious thoughts and drives, psychodynamic theories also discount the significance of self-control, through conscious thoughts and free will.

Nonetheless, Freud remains an influence on proceeding generations of psychoanalysts.

A school of psychologists known as neo-Freudian school sought to further develop his theories. Carl Jung, for a time a supporter of Freud before separating from him, was one such member of this group. Jung noted the role of recurring motifs and symbols in cultural works, which he described as ‘archetypes’. He believed that they influence our ideas and beliefs in a similar way to memory schemas. Freud’s daughter, Anna Freudego defense mechanisms.